The O’Callaghans of Fallagh — and the Kerby Miller Collection

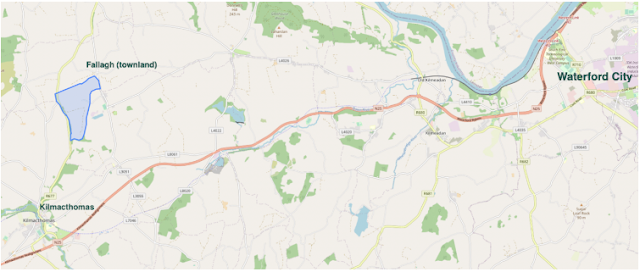

The families of Owen Callaghan and David Flynn in Fallagh townland, just outside Kilmacthomas, Co. Waterford, emerged from the Great Famine with their large farms intact. Owen had died by 1850, leaving his widow Margaret holding their 212 acres, three vacant houses, outbuildings and a valuable dwelling house, all worth £164, making them one of the strongest farming families in the region (in comparison, the neighbouring Flynn farm was valued at £99). Owen, (likely her son), inherited the farm and was among the rate-payers representing Upperthird barony in the county presentment sessions. He died in 1895 aged 67 and by 1901 his wife Kate, with four unmarried adult sons and a daughter remained on the farm, employing two labourers. By then they had adopted O’Callaghan as their official name. It was William, who inherited the farm in turn, becoming a widely respected dairy farmer and progressive agriculturist, until his death aged 80 in 1954. Two years previous, the two ‘esteemed and well known’ Fallagh familes were joined, with the marriage of William’s daughter Angela to David Flynn. Her brother, Eugene, held the farm until his own death in 1985.i

A researcher consulting available public records could surmise that the O’Callaghans were typical big tenant farmers who benefited from the aftermath of the Great Famine to build a successful multi-generational family farm, becoming respected, high-status members of the local community. Thus would probably end our knowledge of this family, were it not for Eugene O’Callaghan’s letter to Professor Kerby A. Miller on 8 January 1978, in response to a local newspaper notice seeking emigrants’ letters.

Gathering the letters

The Kerby Miller collection at the University of Galway Library comprises copies of thousands of emigrant letters sent between the US and Ireland between the late 1600s and 1950s, donated by Prof. Kerby A. Miller. He became interested in the experience of Irish emigrants to America, while studying at the University of California, Berkeley, during the early 1970s. In the many years that followed, he travelled the country seeking letters that had been sent to and from all parts of Ireland and its diaspora. The emeritus Professor of History at the University of Missouri borrowed the original documents, photocopied and transcribed them, before returning the correspondence to their owners, while attempting to gather their background context from the donors where possible.These letters speak of common themes mentioned by Irish emigrants, including advice on the emigration process, sending passage money home, difficulties of adjustment in a new country (including an unfamiliar or often extreme climate with difficult working conditions), coupled with career and family opportunities, homesickness, loneliness, discrimination, racism and strong feelings of Irish (and American) nationalism.

Among them are the twenty-three letters written over 1882-5, between, and on behalf of, members of the O’Callaghan family of Fallagh and provided to Kerby Miller by an elderly Eugene O’Callaghan in 1978.ii Further investigations by Miller led to family history provided by Eugene’s nephew, Liam O’Callaghan in 1990 and more importantly by his niece and amateur historian, Mary Howard (née Flynn), in 1991.

The O’Callaghan’s of Fallow and Philadelphia

The family had long kept the traditional memory of their origins in Bear Island, Co. Cork in the seventeenth century, later relocating to Ballylaneen and then Fallagh in Co. Waterford (with Eugene O’Callaghan claiming that their eponymous ancestor, Timothy Bearach O’Callaghan was ‘a roaring redhead’). David Flynn married into the O’Callaghans from Ballylaneen to become the second farm in Fallagh (known locally as ‘Fallow’) circa 1825. By the early twentieth century, Eugene’s father, William O’Callaghan, was remembered as the only one of twelve children to remain in Ireland, on their 200 acre farm.iii

Boston Public Library

In the meantime, Owen and Bridget had emigrated and were settling in Philadelphia (Owen quickly adopted the O’Callaghan surname in his letters home, unlike his brother). He had financed the passage from Queenstown (Cobh) by the sale of his heifers and sheep in spring 1883, but delayed informing his parents, with their father becoming angry on learning of it. Owen worked as a labourer through 1883, likely at Baldwin’s locomotive factory. In his several letters home he reported on the local rejoicing at the killing of informer James Carey. He asked, ‘how is Newtown getting on’, likely referring to his uncle’s eviction there and was bothered at the difficulty his parents had paying their rent on their farm, especially during a scarcity of farm labourers to bring in the harvest. Owen noted that winter unemployment was high in Philadelphia and work was only to be had through influential contacts or luck. He mentioned that his brother Patt wrote to them regularly from Minnesota and had kindly sent $12.50 for their cousin Stannie, who had just arrived and was staying with them.v

By March 1884, Owen had settled into city life, now working for a blacksmith, with Stannie working in the locomotive factory and Bridget apparently a house-servant in a ‘nice family’. He expressed his delight at learning of the nationalist victories over the landlords' candidates in the recent Poor Law Guardians elections, while reporting on a pleasant night at the St Patrick’s Waterford Ball, even if it was only ‘something like we had at home’. He later told his brother (addressing him as Thomas O’Callaghan), that even with having more jobs and money, he experienced a paucity of fun in Philadelphia compared to the richer social life in Ireland and evening visits to neighbours' houses. Their sister Maggie had joined them in Philadelphia by that May, but Owen had hoped that few would emigrate from the district in that year and ‘have better sense and remain at home’. While noting with approval his parents’ decision to let out their grassland to graziers and thus ‘help to keep the house a bit’, he sadly observed ‘you seem to be doing nothing of late but burying old neighbours’.

By August 1884, Owen was living contentedly in the working-class suburb of Belmont and reported that his siblings were all doing well. An unrecognisable Patt, temperate in nature while looking hardy and suntanned, visited his siblings after being finally discharged from the army. However, he couldn’t settle and soon moved on to San Francisco. Owen’s Christmas letter home confirmed that Maggie had become a ‘regular yank’ in her manners, and everyone was ‘strong, healthy and cheerful’ but lamenting the heavy emigration from the Kilmacthomas area, especially given the sharp reductions in city employment during the winter, with trade strikes against pay reductions.vi

Tragedy in Alcatraz

Patt’s downbeat letter to his father from Alcatraz Island on 29 January 1885 jarred with his brother’s mood. It appears he had re-joined the U.S. Army in San Francisco and while claiming to be in good health, conceded that he had been in ‘a little trouble. But ‘twill soon blow over again’. He wished that he had visited home and family earlier, but still hoped to do so soon while admitting ‘I’m in a poor place at present’. However, shortly thereafter on 19 February 1885, Patrick Callaghan was dead. Owen’s letter home of early May relayed local news while asking after family and friends in Ireland and only in passing advised his father to have patience with his application for his late brother’s back-pay. The final letter in the collection is dated 31 October 1885 from the US military to Owen O’Callaghan (senior), advising him of a payment due of $88.42 in settlement of his late son’s account. Patrick Callaghan was only 26 or 27 years old.viiThanks to Miller’s follow-up research, Patrick’s grandniece revealed that there was a final letter home from him dated 7 February 1885 (not now extant), which advised his sister that he was in very good health but enigmatically warned her against revealing he had reenlisted, to anyone. However, the modern family had no memory of his demise.viii Miller subsequently uncovered newspaper reports that Patrick Callaghan had killed himself with his own gun. Callaghan’s friend, Owen Kennedy, reportedly presented the coroner with a suicide note from the soldier stating ‘I think this is the best way out of difficulties […] I have been victimised, but as far as I know I’ve done nothing degrading to my manhood’. From the conflicting and sensationalised reports, it appears that Patrick had become troubled, relating to an intended marriage to an otherwise unattested woman.ix

Uncle John and the Land League

Mary Howard confirmed to Kerby Miller that her great-grandfather Owen O’Callaghan (senior) had been extremely popular, but despite holding a big farm they were not well off, due to his noted hospitality, in a long cultural tradition going back to visits in the eighteenth century of the Gaelic poet, Tadhg Gaelach Ó Súilleabháin. Howard claimed the family ‘were in the Land League’ while her information can connect the evicted uncle of the Callaghan/ O’Callaghan letters to Owen’s brother, John O’Callaghan of Newtown. He had married into the Newtown farm but was evicted, becoming very involved in the Land League and spending a term in prison.x He was reported as Waterford Farmer’s Club secretary (becoming the Waterford Land League) who was evicted from his 120-acre farm in 1880, for non-payment of rent. After being ‘reinstated’ into his holding by 100 armed men, O’Callaghan was convicted as being complicit in this illegal act and incarcerated in Limerick prison in June 1880. While released in May 1881, he did not recover his farm, though it appears to have been kept vacant for several years.x Cousin ‘Stannie’ was Patrick S. O’Callaghan, John O’Callaghan’s estranged son, who was studying for the priesthood until running away to America, with money borrowed from his uncle Owen.

Why the letters matter

Not all the letters in the Kerby Miller collection contain such detailed and evocative snapshots of the Irish emigrants’ experience and their relationship with their homes back in Ireland. Neither do they all benefit from the additional background information gathered by Miller, which often provides valuable context to the original correspondence.However, all these documents possess one characteristic. They are windows of contemporary insight, no matter how fogged with time, into the world of their authors and intended recipients. The story of the O’Callaghan family of Fallagh humanises what could otherwise be a study footnote in a general classification of late nineteenth/ early twentieth century society in rural county Waterford.

A digital-first project is currently underway at the University of Galway, to curate and publish digitised images of the Kerby Miller collection of Irish emigrant letters to a dedicated online portal, in early 2024. Aside from their own significance for genealogical and heritage studies, these records (even allowing for some only surviving as fragmentary extracts of transcripts) hold tremendous potential to leverage value from other contemporary materials. As in the case of John O’Callaghan, this collection of letters and background research allow connections to be made with disparate events and personalities, using the personal conversations between families and friends, often containing historical information not found elsewhere. Scholars, genealogists, family members and amateur historians are all invited to develop more complete, holistic understandings of the past, using these letters as a gateway to further discoveries.

.jpg)

Joe Linnane's (man holding the paper) famous Radio Eireann Question Time at the Friary Hall in Dungarvan. Sitting beside the man holding the cigarette is Eugene O'Callaghan wearing a Macra Na Feirme badge, c.1950. (Waterford Museum, TT57)

Mary Howard sadly informed Kerby Miller that no photographs existed to accompany the personalities mentioned in the Callaghan / O’Callaghan letters. However, because of the cataloguing work now being undertaken of the Kerby Miller collection at the University of Galway Library, a connection was found to an old photograph surviving in the Waterford County Museum. It is of her late uncle, Eugene O'Callaghan, participating in the audience of a popular radio show that was being recorded in Co. Waterford, circa 1950 (above). This poignantly encapsulates our project mission, to build on the multi-decade efforts of Professor Kerby A. Miller and involving the generosity of hundreds of Irish families throughout Ireland and abroad, to tell the extraordinary collective story of the Irish diaspora, contained within their letters.

Update March 2024: Imirce is now live at imirce.universityofgalway.ie. The Callaghan/ O'Callaghan Letters can be consulted here, along with many other Irish emigrant letters and memoirs written across a period of 250 years.

The launch of the digital repository also includes an open call to the public to contribute new material to ensure the collection's continued growth and relevance. Areas of particular interest are letters written in Irish in North America, and letters and memoirs produced in any language by emigrants from Irish-speaking districts. Details about how to contribute to the collection are available at imirce.universityofgalway.ie/p/ms/contribute.

Author

Liam Alex Heffron is a historian, actor and founder of the heritage charity, St Cormac’s Society. He is working on the Kerby Miller Collection as Postdoctoral Researcher, having completed his PhD examining the revolutionary intersection of land hunger, social justice impulse and memory, in a case study of a west of Ireland community.

Related Links

Blog Post: Imirce is LIVE - Thousands of Irish emigrant letters now available online

Blog Post: A Digital-First Approach for Kerby Miller Collection

Blog Post: Bulk Rename Utility - The Digital Archivist's Lifeline

Blog Post: Curating a Digital-First Collection: Prof. Kerby Miller's Collection of Irish Emigrant Letters

University of Galway Library

University of Galway Library Archives

Images

Image 1: Letter from Patrick Callaghan, Fort Warren, Boston, Massachusetts, to his sister, Bridget Callaghan, Fallow, Kilmacthomas, Waterford (county), 9 March 1882. Archives reference ID: p155/1/1/1.

Image 2: Professor Kerby Miller and his research collection, boxed and prepared for travel during the donation phase to the University of Galway Library.

Image 3: East Co. Waterford. Map based on OpenStreetMap (2023), https://www.openstreetmap.org/

Image 4: Interior of Ft. Warren, George's Island, begun by govt. 1833, completed 1850, [ca. 1863–1870], 1 photographic print : albumen ; 10 x 11 3/4 in., Boston Pictorial Archive at Boston Public Library.

Image 5: Baldwin Locomotive Works, Erecting Floor, 1896. Credit: Arnold, Horace L. ‘Modern Machine-Shop Economics. Part II’ in Engineering Magazine no. 11, 1896, via Wikimedia.

Image 6: Newspaper clipping from San Francisco Bulletin reporting on Patrick Callaghan’s suspected suicide on Alcatraz Island, 19 February 1885. Archives reference ID: p155/1/1/3.

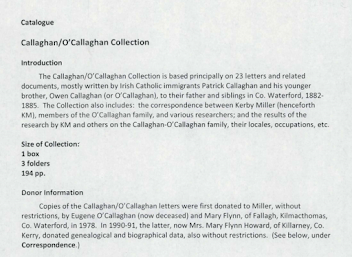

Image 7: Partial first page of catalogue descriptive information for Callaghan/ O’Callaghan Collection, supplied by Professor Kerby Miller. Archives reference ID: p155/1/1/1.

Image 8: Partial first page of catalogue descriptive information for Callaghan/ O’Callaghan Collection, supplied by Professor Kerby Miller. Archives reference ID: p155/1/1/1.

Image 9: Joe Linnane's (man holding the paper) famous Radio Eireann Question Time at the Friary Hall in Dungarvan. Sitting beside the man holding the cigarette is Eugene O'Callaghan wearing a Macra Na Feirme badge, c.1950. Credit: Tom Tobin, ‘Radio Eireann Question Time (Photograph)’, 1950 (Waterford Museum, TT57).

Endnotes

i ‘Tithe applotment records’ in The National Archives of Ireland, sec. Fallow townland, Civil Parish of Mothel, Co. Waterford (1824) (https://www.nationalarchives.ie/article/tithe-applotment-records/) (7 Apr. 2022); Richard Griffiths, General Valuation of Rateable Property in Ireland, Barony of Upperthird, Unions of Clonmel and Carrick-On-Suir, County of Waterford (HMSO, Dublin, 1850), p. 48; ‘County Presentment Sessions - Barony of Upperthird’ in Waterford News and Star, 1 June 1883; ‘Death of Owen Callaghan, Fallow’, Civil records of births, deaths & marriages in Ireland (Carrick-on-Suir District Registry Office, 20 Dec. 1895) (GRO) (https://civilrecords.irishgenealogy.ie/); ‘1901 Census of Ireland, County Waterford - the household returns and ancillary records’, Digital scans of original returns in the NAI in Census of Ireland 1901/1911 and Census fragments and substitutes, 1821-51, sec. Kate O’Callaghan, Fallagh, Ballydurn DED (http://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/pages/1901/Waterford/) (12 Oct. 2019); ‘1911 Census of Ireland, County Waterford - the household returns and ancillary records’, Digital scans of original returns in the NAI in Census of Ireland 1901,1911 and Census fragments and substitutes, 1821-51, sec. Thomas O’Callaghan, Fallagh, Ballydurn DED (http://www.census.nationalarchives.ie/pages/1911/Waterford/) (12 Oct. 2019); ‘East Waterford News - Popular Farmer Passes’ in Waterford News and Star, 26 Feb. 1954; ‘East Waterford News - Wedding Bells’ in Munster Express, 28 Nov. 1952; ‘Kilmac Notes - Late Eugene O’Callaghan’ in Munster Express, 18 Oct. 1985.

ii ‘Eugene O’Callaghan, Fallagh, Kilmacthomas, Co. Waterford to Dr K.A. Miller, Institute of Irish Studies, Queens University, Belfast’, 8 Jan. 1978 (KMA, p155_0001_0001_0002-0003-4).

iii ‘Liam O’Callaghan, Co. Waterford to Prof. Kerby Miller’, 1990 (KMA, p155_0001_0001_0002-0010-11); ‘Mary Howard (nee Flynn), Co. Kerry to Prof. Kerby Miller’, 5 Feb. 1991 (KMA, p155_0001_0001_0002-0023-31)

iv ‘Patrick Callaghan, Fort Warren, Boston, Massachusetts, to his sister, Bridget Callaghan, Fallow, Kilmacthomas, Waterford (county)’, 9 Mar. 1882 (KMA, p155_0001_0001_0001_d001); ‘Patrick Callaghan, Fort Warren, Boston,Massachusetts, to his brother, Owen Callaghan, Fallow, Kilmacthomas, Waterford (county)’, 14 July 1882 (KMA, p155_0001_0001_0001_d002); ‘Patrick Callaghan, Battery F, Fourth Artillery, U.S. Army, Fort Snelling, Minnesota, to his sister Maggie Callaghan, Fallow, Kilmacthomas, Waterford (county)’, 14 May 1883 (KMA, p155_0001_0001_0001_d005); ‘Patrick Callaghan, Fort Snelling, Minnesota, to sister Maggie, Fallow, Kilmacthomas, Waterford (county)’, 17 Aug. 1883 (KMA, p155_0001_0001_0001_d007).

v ‘Owen Callaghan, Fallow, Kilmacthomas, Waterford (county), to his sister, Bridget Callaghan, Dungarvan, Waterford (county), 28 February 1883. Short note, appended to the end of the letter by Maggie, who forwarded the letter to Bridget’, 28 Feb. 1883 (KMA, p155_0001_0001_0001_d003); ‘Owen O’Callaghan, Philadelphia, to his sister Maggie Callaghan, Fallow, Kilmacthomas, Waterford (county)’, 3 Aug. 1883 (KMA, p155_0001_0001_0001_d006); ‘Owen O’Callaghan, Philadelphia, to sister Maggie Callaghan, Fallow, Kilmacthomas, Waterford (county)’, 17 Sept. 1883 (KMA, p155_0001_0001_0001_d008); ‘Owen O’Callaghan, Philadelphia, to his father, Owen O’Callaghan Senior, and his sister, Maggie, Fallow, Kilmacthomas, Waterford (county)’, 5 Dec. 1883 (KMA, p155_0001_0001_0001_d0011).

vi ‘Owen O’Callaghan, Philadelphia, to his mother, Kilmacthomas, Waterford (county)’, 26 Apr. 1884 (KMA, p155_0001_0001_0001_d0012); ‘Owen O’Callaghan, Philadelphia, to his brother, Thomas O’Callaghan, Fallow, Kilmacthomas, Waterford (county)’, 27 May 1884 (KMA, p155_0001_0001_0001_d0013); ‘Owen O’Callaghan, Belmont, Philadelphia, to his mother, Fallow, Kilmacthomas, Waterford (county)’, 24 Aug. 1884 (KMA, p155_0001_0001_0001_d0015); ‘Owen O’Callaghan, Belmont, Philadelphia, to his sister Ellie [Ellen?] Callaghan, Fallow, Kilmacthomas, Waterford (county), 2 November 1884. Short note, appended to the end of the letter by Ed Kirwan, Belmont, Philadelphia, to Thomas O’Callaghan, Fallow, Kilmacthomas, Waterford’, 2 Nov. 1884 (KMA, p155_0001_0001_0001_d0016); ‘Owen O’Callaghan, Philadelphia, to his brother, Thomas O’Callaghan, Fallow, Kilmacthomas, Waterford (county)’, 12 Dec. 1884 (KMA, p155_0001_0001_0001_d0017).

vii ‘William A. Day, U.S. Treasury Department, Washington (D.C.), to Owen O’Callaghan Senior, Fallow, Kilmacthomas, Waterford (county), 31 October 1885’, 31 Oct. 1885 (KMA, p155_0001_0001_0001_d023); ‘Owen O’Callaghan, Philadelphia, to his brother Thomas[?] O’Callaghan, Fallow, Kilmacthomas, Waterford (county)’, 8 May 1885 (KMA, p155_0001_0001_0001_d0021); ‘[Name illegible], Assistant Adjutant General, Adjutant General’s Office, Washington (D.C.), to Owen O’Callaghan Senior, Fallow, Kilmacthomas, Waterford (county’, 10 Apr. 1885 (KMA, p155_0001_0001_0001_d019); ‘Patrick Callaghan, Alcatraz Island, California, to his father Owen O’Callaghan Senior, Fallow, Kilmacthomas, Waterford (county)’, 29 Jan. 1885 (KMA, p155_0001_0001_0001_d018); ‘Patrick O’Callaghan’s official discharge paper from the U.S. Army, at Fort Snelling, Minnesota’, 10 July 1884 (KMA, p155_0001_0001_0001_d014).

viii ‘Letter, Howard to Miller, 1991-02-05’.

ix ‘A Mysterious Missive’ in San Francisco Chronicle, 19 Feb. 1885; ‘Supposed Suicide’ in San Francisco Bulletin, 19 Feb. 1885.

x Donnchadh Ó Ceallacháin, ‘Land Agitation in County Waterford, Part 1’ in Decies: The Journal of the Waterford Archaeological and Historical Society, no. 53 (1997), pp 97, 126–7; ‘Released’ in Waterford News and Star, 7 May 1881; ‘Forcible Entry’ in Waterford News and Star, 24 Dec. 1880; ‘Summer Assizes — Malicious Injuries’ in Waterford News and Star, 27 July 1888.

Comments